Right, it’s a loose link between the sorts of books that I love and the time of year that implores your local neighbourhood to deck their front hedging in fake spiderwebs and skeletons that will laugh as you go by, but bear with me. (**Posting this well into ~Scorpio Season~ after having missed my Halloween opportunity almost entirely, but forgive me, because I’ve been slogging 85 hour weeks in production for Vietgone – which opened for previews at the Playhouse, QPAC on Saturday night and is a bloody masterpiece if anyone from Brisbane is looking for some sharp, electrifying, transcendental theatre in the next fortnight. I’m sure I’ll write a whole other blog about it. If I find the time.)

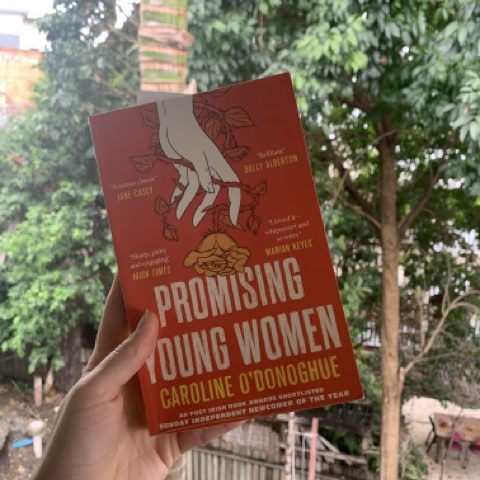

Caroline O’Donoghue – Promising Young Women

I promised I’d write to you about Caroline O’Donoghue again! I was lucky enough to meet this charming and brassy dame thrice over an evening, at her “In Conversation” with Queensland Writer’s Festival a few weeks ago. I got the chance to shower her in rambling compliments and offer her the spare room in my Petrie Terrace share house when I bumped into her in the gift shop beforehand, and enjoy that very special experience of sharing with a writer something they’ve written that moved you (read: throttled, impaled, derailed).

I’d finished reading Promising Young Women the day before, and was haunted by the centripetal climax of a relatable yet foreboding story that was so gently palatable to first sink my teeth into. O’Donoghue later described it that evening as, “I was trying to write a gothic novel… something that began a bit Marian Keyes or Bridget Jones’ Diary, like a girl in the city story, and for it to become a bit more like an Angela Carter or Daphne du Maurier,”

If this was the goal, she nailed it. She toyed with my trust, and lured me into suspicion in the frothy, genial story of modern young ladies – ladies I know, ladies I might make mistakes akin to. The story insidiously burrows into deeper and darker places not unlike the haunting of stories like the original Gaslight (1944). What’s real? Who’s to be believed? How much do you have to trust your narrator? How frightened am I for them, and are the stakes just in their head? Caroline’s greatest strengths as a writer (and as a podcast host) lie in metaphor and propulsive imagery – she paints very real worlds through a lens barren of cliches, inviting new perspectives, holding you hostage within the point of view of your protagonist. Plot points sat in unsuspecting homonyms, pitting phrases on the reader, first comfortably and then disconcertingly. Without spoiling a gimmick that wholly drew me in, plenty was not as it first seemed.

My question to Caroline in the Q&A session of the evening was about how she approaches plot in her stories. Her novels all have this inimitable trajectory of forward movement – an exponential reach toward the third act. The sort of pace and action I’m starved of across much modern writing. Her answer was so classy.

We’ve all read a book or two in the last year where we felt like nothing happened, know? I think it’s lazy. Do better. Commit.

In answer to the question of how, she landed on “practise.” It’s evident to me across her three novels for adults that her skills are sharp and her incisions clean. The tidy and satisfying endings to her novels are sating an appetite of mine that has long gone starved.

Thank you Caroline, my old friend.

For lovers of London’s 24 hr tube schedule on a weekend, impressing roomfuls of men in corporate meetings and cheap French wine from Tesco. Pairs nicely with the impulse for a career change, or curling up in bedsheets that you remember to change weekly.

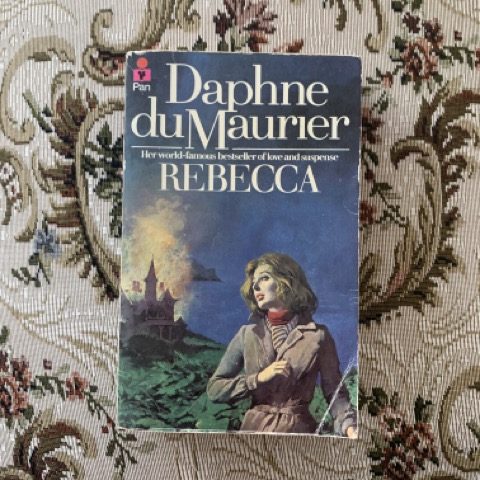

Speaking of Daphne du Maurier, let’s talk about Rebecca.

I recently bought a copy at the Lifeline book fair because even though I’ve read it, I added it to the library so I’d have one handy if I ever needed to prescribe it.

This novel has two movie adaptations, the first of which I treated myself to after finishing the novel. Hitchcock’s noirish adaptation lead by Laurence Olivier and Joan Fontaine, and underscored by a taut and bitter Judith Anderson as Mrs Danvers was made early enough in his career (1940) for me to sleep with the lights out that night, but to plague my waking mind for days to come. The 2020 Netflix movie adaptation with Armie Hammer, Lily James and Kristin Scott Thomas was set up to be a sleek, stylish and lush period adaptation, and my excitement was quickly quelled by naff dialogue and panto foreshadowing in the first 20 minutes of the film, compelling me to switch it off, lest I tarnish how much I marvel at the source material.

This book is a masterclass in the slow burn. It begins with inimitable beguile, landscapes and garden arbours worthy of verbose drawl in their descriptions work as an almost hypnotic element, latching you tightly into the POV of the unnamed narrator. The first chapter opens with the line, “Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again,” pitting the retrospect as dreamy and through rose coloured glass, rendering our image of Manderley and its blood red boughs of rhododendron as wistful and intangible. A meditative and psychological mystery infolds in steady pace between our Narrator and the handsome, enigmatic Maxim, upon a coastline whose imagery will remain seared into your brain until long after you but the book down.

For lovers of the sounds of the ocean in dense, rainy weather, and the sort of old-money living room that’s decked in family portraits. Pairs nicely with a good English rose garden, or a cosy sitting room in candlelight (with a fire blanket close by.)

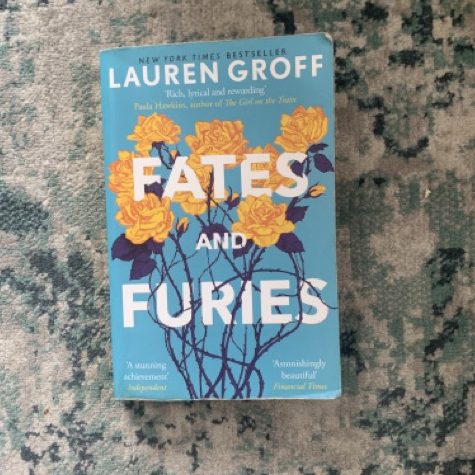

Fates and Furies by Lauren Groff

I fronted my book club with this choice over the weekend after having read this book and audibly gasped throughout more than I think I ever had with a piece of literature. My questions to the comrades that I desperately needed help answering were: was this a horror? Was it a love story? Was I just gullible or was it some of the most surprising storytelling out there? At what point in the romance did you to begin to suspect there was a whole underbelly of lies underpinning the earnest POV of our first narrator?

I dare not spoil this book, as its magic again lies in its insidious unravelling. It’s a slow burn, (noticing a theme?) rich, dense, lyrical. You can wonder how much of what you’re reading is necessary or just clutter, before you realise that Groff is using the density to drag you into the depths with her and to cloud your judgement, to beguile your trust and to trick you. There is an eighty page section toward the middle of the novel that reads like a Dostoyevskian epic set at an artistic retreat which was gruelling to read. I felt assaulted by the inner-workings of the sort of creative “genius” I often find myself surrounded by in my world. The workings of paranoia and desperation trickling through one protagonist’s strife, quelled or impelled by our second narrator – who’s to say?

As someone who is well and truly submerged in the industry of theatre, I am suspicious of writers who fuse the forms of literary prose and theatrical script; suspicious of whether the claims to its genius stand through a lens whom has seen plenty fail and flop upon the stage from its nuclear development stages. But Groff navigates the identity of our writer characters with adroitness and sleight of hand. Like a card trick, she’s telling as much of the story in what she’s withholding as what she shares, whether you notice it or not.

For lovers of New York, opera (or despisers of), and retribution. Pairs nicely with the aftermath of a potluck apartment party, the plight of bohemian poverty.

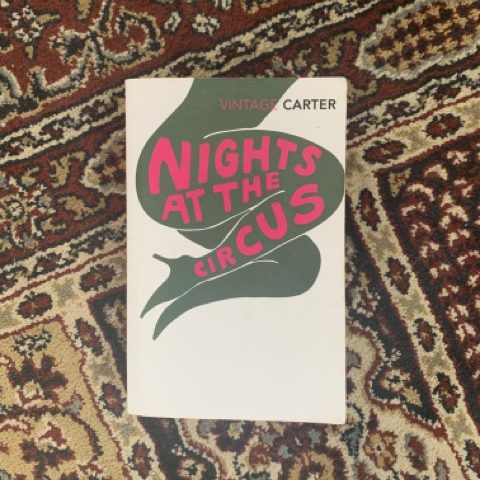

Nights at the Circus: Angela Carter writes like a woman in charge.

She writes like a woman working the room, orchestrating the dynamic, averting your eyes from the horrors. Frivolous soliloquies masking the darkness. Marionetting your reactions to the story our charismatic storytellers are artfully driving.

This story exists in a palpably real historical world, peppered with a surrealism that baits the readers gullibility. Sophie Fevvers is a showgirl and celebrated aerialist named for the backstory she purports: a virgin woman hatched from an egg, with real life goddamn wings. The first hundred or so pages are the one scene: Sophie mopping makeup off her face in the dressing room after a show, in candid conversation with an American journalist sure to fall in love with her.

It’s officially a novel of postmodernism and post-feminism, which are claims that I will buy amid my fastidious research of the novel, but not themes that seemed overly conspicuous in the story at the time. Its subtlety and artful distraction along the magical-realism story itself are all that I could really believe about it. Whether this woman had feathers or not – and, in turn, what Carter was trying to say with these claims – could only be left to interpretation.

For lovers of theatre, spectacle, candour and frivolousness, and for those of you who barbarously enjoy the grotesque. Pairs nicely with popcorn or hearty Serbian cuisine, and stamina.