I have never been one to reread books. I have this heady presumption that clever, learned people are widely read (sometimes in place of well-read), and approach a reading list like I always have to make up for lost time. (How many years am I going to go on, continuing to be a woman who can’t substantiate her reference to Dickens in conversation? Virginia Woolf? Hemingway?)

Frankly, none of us who have any vocation out side of literature can keep pace with the rate at which the world both celebrates old books and births new ones, and you have to give yourself permission to develop taste (put down the Bukowski, 19-year-old Bridget), and permission to reach for the old faithfuls like you did when you let the old VCRs of your childhood just start again from the beginning on those aching, rainy days.

I often use the phrases, “I wish I could read that again for the first time all over again,” or “I’m so jealous you get to watch this for the first time!!” to articulate how uniquely eviscerating, epiphanous or orgasmic something wonderful can be at that very first ephemeral moment of acquaintance. It’s a useful metric to gauge the value something might hold for you over the time that passes thereafter.

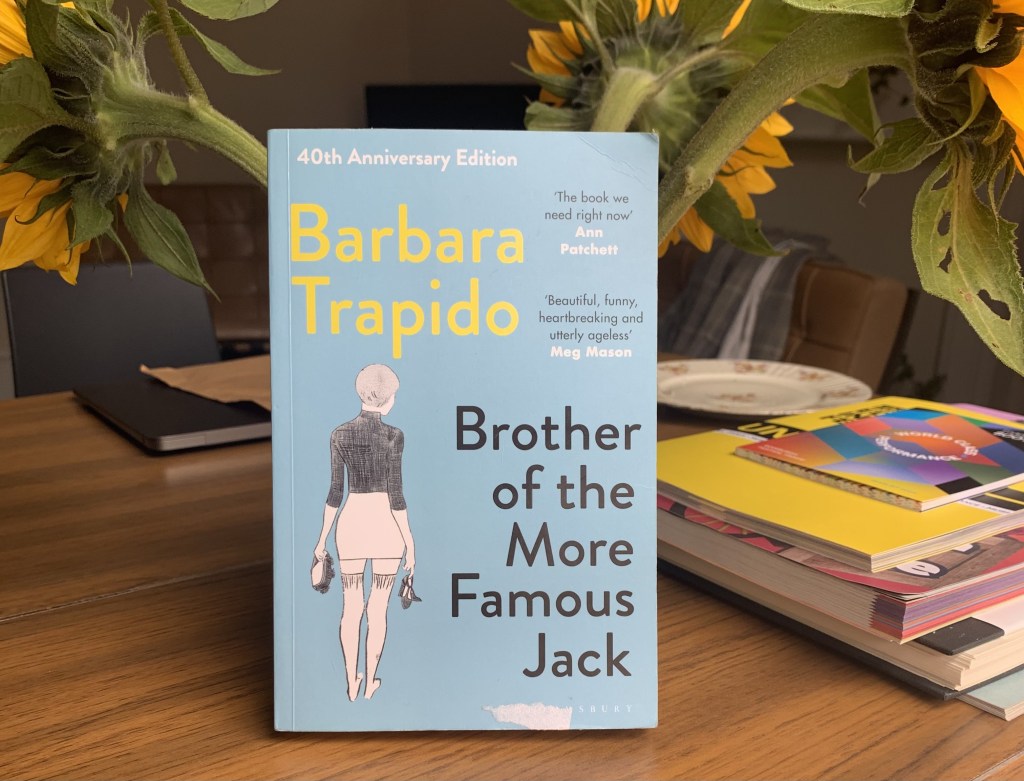

I recently had this first-time, ingenuous, starry-eyed meet-cute with something truly wonderful. Except that we had absolutely met before. Old flame Barbara Trapido walked back into my life, bringing with her the fictional entourage of the Goldmans. My, it was nice to see them again.

Memory is a funny thing. I am latched to the Shakespeare soliloquies I learned at 15, they can tumble out of my mouth like muscle memory. But days after some university exam recitals, I couldn’t even quote you the lyrics of the text I’d been learning for months. A wise friend shared pithy advice with me not long ago. Each moment possesses three layers: your experience, your awareness of the experience, and the story you tell about the experience. I’d like to argue that between “the experience” and “the story” exists an infinite spectrum of what could possibly be taken away; varying degrees of attention, perception, reality, bias, and mutation can manipulate the moment each time it is ever remembered. I find this a wonderfully convenient excuse for all of the meaningful things that time ever warped, wasted and forgot.

When I was 18 and first read Barbara Trapido’s Brother of the More Famous Jack, I walked away with memory of the experience – equal parts impressionism and infection – that dared to define my early twenties. It defined them in a way I almost completely forgot.

I didn’t really remember what happened in the novel. I remember it sparking a desperation to be learned, as substantiated above. It gave me a self congratulatory smugness about my Shakespearean rote recitations. I remember thinking it silly that two main characters would effectively share a name in the same plot, and vowing never to fall into that trap as a writer myself (John, Jonathon, Jont., etc.). I remember being impressed by the tactfulness and decorum of an author writing so convincingly a character who is obviously beautiful, without any accompanying vanity to make me dislike them. I remember being charmed by the name Simonetta and wondering, ‘Where do I remember that from?‘ every time I’ve ever seen a Botticelli painting since. (When you spend as much time in Italy as I have, this comes up a bit.)

I didn’t think about it for years.

Later when I interrogated the trajectory of my life (or more likely was being interrogated by a confounded friend or family member or fresh acquaintance) I had to answer a question about why I relentlessly keep pursuing a continental life. Why Italy? What planted the seed? For a long time I justified that the idea came from some old Labor Government rule that a HECS debt was rendered void after one had lived a certain amount of years in another country. Maybe it’s because I grew up so spoilt in such a comfortable home that I never felt all that attached there. But maybe it has something to do with heroine Katherine Browne snapping and setting off, expunging years of her life in Rome to transcend her own grief. Or maybe it had more to do with The Lizzie Maguire Movie.

Now I confess I have lived my life with varying relationships to the memories time has made. I’m liable to misconstrue and over-keel the balance. But this unreliable narrator in my head whose forgetfulness is usually just a nuisance gave me the most precious gift. A clean slate to meet the Brother of the More Famous Jack again for what earnestly felt like the first time.

The preciousness and deliciousness of this book lies chiefly in the wit and charm of its characters. (How much pretentious bullshit must I have been reading at the time to overlook the incendiary scene making between these florid, nuanced and rich characters??) The story casts a delicate, malleable lens upon class barriers, and the parameters of unconventional relationships. It gives such wide breadth to the evolution of unprecedented friendships and humanises the eventualities: comfortably reaching amicable ends for our characters while crafting allusions futures that leave us with a comforting hope. A melodic through-line courses through the book in the form of amorphous language: harmonies of crassness, politeness, witticisms and probes dance about in both a symphonic cymbal clash and the consonance of a string section; a satisfying opus. There is a lushness to the discovery of new places and a similar, due reverence put upon the exoticism of Trastevere to an outsider and the harvest of parsnips from the garden at a family’s country home. The womanly identity is allowed to learn as much from the pretentions of a philosophy professor as his wife’s culinary labours, and the growth of the impressionable girl (both the one reading the book and the one helming the narrative) is organic, palpable and relatable.

There is no greater delight than finding my former self in the retrospect: watching an ingenue like Katherine sidestep her familiarities and humbly take on the hardship of a life both delicately and thoroughly lived, seeing both worthiness and solidarity in a path that extends outside ones bubble to build themselves up. I can’t help but admit that this book has influenced my relationship with home, with trying to manipulate how the world sees me, with valuing the wisdom of those older than me and generous enough to pay me their attention. Finding my religion within these pages has come as an anchoring comfort in a time of unanswerable questions.

The same wise friend mentioned above recently called me out on having a real issue with loving the drama of external factors like books, film, music to shape you rather than letting natural human growth shape you. To this I quipped that perhaps it’s because I feel more like a fake person than a real person? He says, perhaps you feel too real and wish to be a fake person so that all your problems can be fake and fixed by clever writing.

That is PRECISELY what I wish. Doctors orders.

And because I’m a homemade moonshine cocktail of moxie, tact and a self indulged belligerence, I’m building a dossier – like a zodiac chart or a diagnosis – of the culture I have to blame for being the way that I am. Culture to dive back into, to revisit like a comfort blanket when you feel hazy or lost or hopeless. Pursuit of the new can sit on the bench and wait for recapitulations to take their turn. The woman I was at eighteen versus the one I am now at twenty-six garnered connection with this novel in ways that will no doubt differ from my relationship with it at thirty-one and fifty-five. I will reread Little Women annually, if I so please. I’ll rewatch High Fidelity, Bridget Jones’ Diary, Ladybird (specifically the Streisand-inspired audition scene), and my inner monologue will warp toward the self-indulged and self-deprecating. I’ll binge Before Sunrise, When Harry Met Sally, the dinner table scene that opened Fleabag’s second season, and I’ll poach pieces of dialogue to try out on unsuspecting strangers. Revisiting the fictional places that feel like home is a way of nurturing the little girl within me. I’m nurturing my impressions, my memories. Giving them permission to age like wine and fertilise my identity’s springtime.

The point I’m coming to is this: I recommend this book. Heartily. It will change your life. But more broadly I recommend permitting oneself to find gospel in art. People possess a primal need for devotion and guidance and I encourage you to surrender to it. Let the things you love matter to you. And let them impel you to move to Italy if it so comes to it.

For lovers of a new recipes from old cookbooks, artfully thrifted fashion, and spontaneous uprooting to foreign cities, this book pairs beautifully with a garden salad so fresh that is still bears some remnants of from whence it was plucked, and lively dinner party conversation that crosses a line or two, and sitting by quietly, incubating the most eloquent, perfectly timed response.